Share

Human Rights Voices

While the UN devotes its human rights operations to the demonization of the democratic state of Israel above all others and condemns the United States more often than the vast majority of non-democracies around the world, the voices of real victims around the world must be heard.

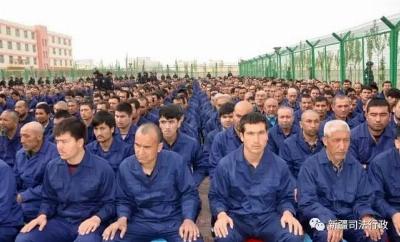

China, December 18, 2021

Uyghur women in China labor camps recall horror of rape, forced sterilization

Original source

In 2017, Tursunay Ziyawudun was arrested off the street in northern China’s Xinjiang region, forced by police officers to turn over her passport and taken to a prison camp about 30 minutes from her village. There, she was made to sing communist songs of patriotism and repeatedly told that her Muslim religion does not exist. After a month, she developed stomach issues, fainted and was released.

“They sent me to the hospital,” Ziyawudun, who came to the United States as a political refugee in 2020, told The Post. “If they hadn’t I might have died.”

The year after she was arrested off the street, still in China, she was summoned to a police station and told that she needed to complete her training. She was sent back to the “re-education” camp, where her hair was shorn — likely to be sold as a wig — and her earrings were ripped out. “They pulled it so hard that my ears were bleeding,” Ziyawudun recalled. “I was being treating like an animal.”

Breaking down and crying, she said: “I was gang-raped and my private parts were tortured with electricity. You’re left with marks on your body that make you not want to look at yourself.”

“They gave me sterilization pills,” said Ziyawudun. “I am pretty sure that is why I cannot have a baby now.”

Her story is, tragically, not uncommon for members of the minority Uyghur religion, with Turkish roots, in President XI Jinping’s China. Since around 2016, they have been pulled off the street and sent to reeducation camps — where reports have surfaced about people being tortured, raped and even killed. They are sent there under the auspices of learning a trade and having their patriotism reinforced.

On Thursday, the US Senate followed the House’s lead in passing the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, which promises to ban imports coming from the Xinjiang region — home to some 12 million Uyghur people — unless there is proof the goods were not produced by forced labor. It’s now waiting to be signed by President Biden.

Amelia Pang, author of “Made in China: A Prisoner, an SOS Letter, and the Hidden Cost of America’s Cheap Goods,” acknowledged that the act is a huge deal that “hurts China’s plan. China has invested a lot of money into making an important trade route [that goes through Xinjiang] a key part of what is called its Belt and Road Initiative. It’s a trillion-dollar project to connect China to Central Asia and Europe and the Middle East. It’s almost too big to fail.

“They are afraid of an uprising in the region. They are so afraid of losing out on their investment.”

But she pointed out that, to be effective, the act needs the teeth of corporate executives: According to a study published by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, companies such as Nike, BMW and Apple use components and materials produced directly or indirectly by forced labor.

“The supply chain is murky … and there is not a whole lot of accountability,” Pang told The Post, adding that large corporations often look the other way and avoid asking the right questions. “They need to think about whether the money they are paying [for manufacturing] can realistically meet the wages from that region. Factories follow the bottom line and outsource to prison camps where workers are basically slave labor.”

An Apple spokesman told The Post, “We conducted over 1,100 audits, including surprise audits, and interviewed more than 57,000 workers to insure that our standards are upheld … We have found no evidence of forced labor anywhere in our supply chain.” Representatives for Nike and BMW did not respond to requests for comment.

The next time you’re tempted to purchase a pair of leather gloves made in China, think of Gulzira Auelkhan. She spent two and a half months in a forced labor camp near the country’s northern border, working for pennies per hour stitching gloves.

“There were cameras and police and you could not sit,” she told The Post. “I worked constantly, 14 hours a day, and was yelled at so much that it began to feel normal.”

Amazingly, what kept Auelkhan, who received political asylum in the United States earlier this year, from slowing down on the assembly line was a fear that she would be relieved of her labor.

“If you said you did not want to work, you went back to the [prison] camp, where you would be tortured,” she said. “I felt like a slave but it was better than being in the other camp.”

Indeed, Ziyawudun recalled the looming threat of being summoned to a space that women in her prison camp referred to as “the dark room.”

“We were all scared of it. When the police wanted to threaten us, they’d say they were going to take us to that room,” Ziyawudun said. “Anything you can think of, including rape, takes place in that room.”

Pang is not surprised: “Rape is pretty standard in forced labor camps,” she said. “The goal is to brainwash prisoners into being patriotic and extremely aligned with the Chinese state.”

Bob Fu, founder and president of China Aid, an organization with the mission of advancing religious freedom in China, was told by a former prisoner that the sexual brutality comes with a commercial component.

“We rescued a woman who was eyewitness to a program that the government organized for prostitution,” Fu told The Post. “She was handcuffed to the bed, the man did his thing and she cried. She said she heard the man shouting and complaining that he had paid good money for this and she was crying.”

Fiendishly convenient for the Chinese, according to Kuzzat Altay, CEO of Cydeo, an international software-coding boot camp, the use of forced labor in hundreds of camps and factories scattered around the country allows the Chinese government to undercut manufacturing costs around the world.

“China keeps prices low and Americans keep buying Chinese products cheaply,” said Altay, a former resident of Xinjiang who moved to America in 2008 and is an outspoken opponent of the country’s human right abuses.

“China’s entire supply chain of manufacturing involves forced labor. They make shoes, pants, solar panels in these forced-labor factories,” he told The Post. “The Chinese economy is a vehicle for oppression and a source of influence in Silicon Valley, Hollywood and Wall Street. That money comes from slavery.”

Altay’s 67-year-old father was kept in a prison camp for two years, held there, supposedly, so the government could teach him a trade that could help the Communist Party.

For two years after, Altay said, “I did not know if he was alive or not. I cried every day. It was mental torture.”

Fortunately. Altay’s father emerged with his organs intact. “Organ harvesting is normal in the Chinese Communist Party,” Altay said. “They are known for this. There are some rich Middle Eastern clients who want Muslim kidneys” — which are free of alcohol and pork. “So Uyghur people were having their kidneys taken.”

In 2019, a group called the China Tribunal offered testimony to the United Nations Human Rights Council, maintaining that “forced organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience has been committed for years throughout China on a significant scale.”

Altay views this as more than pure cruelty — saying it’s also a form of slow-motion genocide. “The women get sterilized because the Chinese government wants to minimize the Uyghur population,” he said. “Right now the population growth is almost zero percent. In 10 years it will be zero.”

Chinese government spokespeople have denied this.

Pang believes that the way to help put a stop to all of it is for Western consumers to stop buying goods that have been made with forced labor — a movement she calls “ethical consumerism” — and for the Nikes of the world to respond appropriately.

“If it’s not lucrative for the Chinese factories to use forced labor, if they can lose major contracts,” she said, “it will have an impact on these camps.”

And it will allow American manufacturers to compete on a more level playing field. As Altay put it: “You buy something made in China, you are giving China a bullet to shoot back to America.”