Human Rights Voices

While the UN devotes its human rights operations to the demonization of the democratic state of Israel above all others and condemns the United States more often than the vast majority of non-democracies around the world, the voices of real victims around the world must be heard.

United Arab Emirates, August 25, 2015

Canadian family pleads for father detained in the United Arab Emirates: ‘torture until I wished for death’

Original source

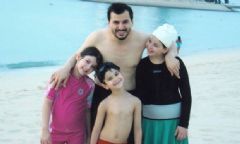

Marwa Alaradi sometimes slips into the past tense when she describes her father Salim, who has spent 362 days in a cell somewhere in the United Arab Emirates, detained without charge and allegedly tortured, the prisoner of state security agents who for months refused to tell his family whether he was dead or alive.

"He was a good father," the 17-year-old said. "He used to talk with us about life, how to be a good person. At the last meeting we had in the hotel, I remember him saying: 'Honesty brings goodness'."

At around 2am on 28 August 2014, Salim Alaradi received a call to his hotel room in Dubai, where he was on vacation to visit family. The caller asked the Canadian-Libyan citizen to step downstairs to answer a few questions. Salim never made it back.

"We knew that he did nothing wrong, but it's the national security service so it's hard to find out anything. We didn't know whom to contact or talk with."

Alaradi was finally allowed to call to his family, who had spent two months and 11 days "crying and praying" for information. He asked after them before they went back to the family home in Vancouver, but he didn't know where he was or why he was arrested, and said he was allowed no lawyer nor access to the Canadian consulate.

"It was very surprising – we were happy just to hear his voice," his daughter said.

On the same night, agents in the UAE also seized nine other Libyan men, including Alaradi's brother Mohamad, who only has Libyan citizenship. "They blindfolded me, tied my hands, and put me in a black car. Then they took us to the secret prison," he said.

Asked almost immediately by agents, Mohamad denied any participation in the Muslim Brotherhood, and torture and beatings began in short order, he said. "They attached me to an electric chair, and beat me all over my body. They put like machines on my hands – on my nails – tied to my nails. They banned me from sleeping for nine days – and I stayed standing with barely any food.

"I asked them about my rights. They said, 'You don't have any rights. You are under our control and nobody in the world can help you.' On the first day, they told me: 'We're going to torture you until you wish you were dead – but death won't come.'

And they kept their word – they tortured me until I wished for death."

With the help of a cousin, Dr Abdulssalam Aradi, the family appealed to Canadian authorities for help. Canadian officials were able to visit three times over several months, he said: once at a distance, and twice more in conversations chaperoned by state security. Requests to speak with Alaradi alone were denied, he said.

The family suspects that the UAE only allowed interviews with Alaradi over several months so that signs of torture could heal. They described varied and vicious tortures: truncheon beatings, lashes with a leather cord, waterboarding, sleep deprivation and solitary confinement. Alaradi's brother said that interrogators told him his mother was about to die; that they would rape his daughters; that the screaming he heard through the walls was his kin.

"The thing that still doesn't let me sleep at night," he said, "what makes me cry is not my torture, it's hearing the sounds of my brother being tortured. He would scream and cry. And I knew I couldn't help."

'It's really out of hand now'

Human rights activists and researchers say the account fits a broader, expanding pattern of arbitrary detentions and torture allegations since 2012.

"This is part of an ongoing trend in the UAE," said Nick McGeehan, a researcher for Human Rights Watch. "We have documented numerous cases of torture in the United Arab Emirates, and it would seem beyond doubt that there is a state security prison where people suspected of seditious activity, if you want to call it that, are held extralegally and interrogated."

McGeehan estimated that between 100 to 200 people have been detained since 2012, many without any political affiliations.

"It's really out of hand now," said Drewery Dyke, a researcher for Amnesty International, which in 2014 published an 80-page report that condemned the UAE's "uncompromisingly repressive" actions.

"The interrogations seem to be somewhat systematized, almost scientifically done," Dyke said. "What Salim and Mohammad reveal is really quite a tragic story about the Emirates. Hidden behind the face of the modern UAE, the Burj Khalifa, the Burj Al Arab, there is another kind of modern reality, which boils down to the severe ill treatment of innocent people."

He suggested American, Canadian and European officials were loath to unsettle trade and counter-terrorism agreements with the UAE and similar Gulf monarchies.

Mohamad was released after four months and promptly deported: authorities put him on a flight to Istanbul with no money, only his passport and clothes. "They realized that they'd made a mistake, that I had nothing and knew nothing.

"I don't want to damage the name of the Emirates, or harm its reputation with my words. But I want those responsible, and the rulers, and the good people of the Emirates to face the fact that they have secret prisons where people are tortured."

According to Mohamad, interrogators mostly asked about Libya. "All the leads go there," his nephew said, "The UAE was thinking that Libyans they arrested could be tools to put pressure on factions that the UAE is not supporting in Libya."

The UAE is actively involved in the chaos of post-revolution Libya, where the Alaradis have a brother, Abdul Razak Alaradi, who was a member of the transitional government and in a party linked to the Muslim Brotherhood.

Last August, American officials accused the UAE and Egypt of flying air strikes on Libyan factions, and the UAE and Qatar have paid for and supplied arms to groups there for years.

Since the aftermath of the Arab spring, the UAE has steadily increased pressure on suspected dissidents, activists and foreign nationals. Authorities arrested 41 people in early August on charges of sedition; 30 Libyan nationals last August (including the Alaradis); and in 2013 accused 94 people of plotting a coup.

Last week the UAE detained academic Nasser bin Ghaith without charge, making him the latest in a string of arrests, detentions and convictions of people who have criticized the government.

The family maintains that neither brother, businessmen with a global electrical appliance company, have any political affiliations.

A spokesperson for Canada's Ministry of Foreign Affairs said only that senior Canadian officials are in contact with Emirati counterparts, and that "consular services are being provided to the Canadian citizen."

Repeated calls and emails to the UAE's foreign ministry, mission to the UN and embassies in Ottawa and Washington were not returned.

The Alaradis in Canada continue to hope for his release. They sent an open letter to prime minister Stephen Harper, and Marwa manages an online petition and social media campaign while also dealing with the trials of every teenager: homework, friends, family.

She said her mother tries to act normal for her youngest children, aged four and seven. "We don't want them to feel like their father is gone, and we don't even know where he is or how he's treated," she said.

"It's been very difficult. Sometimes she goes to her room and cries, she can't hold it anymore. My father deserves to come home."